Companies that offer earned wage access, aka on-demand pay, have proliferated in the U.S. Now, legislators and regulators are targeting the industry for more oversight.

Published Nov. 2, 2021 - HR Dive

Lynne Marek, Senior Editor

UPDATE: Nov. 4, 2021: At a congressional hearing Tuesday, industry organizations offered testimony before the House Financial Services Committee's Task Force on Financial Technology regarding the benefits and potential detriments of earned wage access and other new fintech consumer services, such as buy now-pay later installment payment options. House members of the task force questioned the witnesses and offered dueling interpretations of EWA and BNPL offerings.

Innovative Payments Association CEO Brian Tate called EWA services “safer, cheaper and more efficient,” while National Consumer Law Center Associate Director Lauren Saunders reiterated some of her concerns. “We do have troubling indications that there are a number of consumers who are late who may be struggling and I am also worried whether some of the providers may be building profit models on those late fees," she said.

-----------------------

The mushrooming on-demand pay industry is attracting increased regulatory attention from state regulators, and now consumer advocates are pushing the federal government to take a harder look too.

Payactiv, PayDaily, and Even Responsible Finance are among the biggest companies that have sprung up over the past decade to offer employees access to their wages before payday. While these companies provide the service through employers, some companies offer a variation directly to employees.

A coalition of 92 consumer protection groups, including the National Consumer Law Center, the civil rights organization NAACP and the Center for Responsible Lending, took on the industry last month in a letter to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. They called on the federal agency to protect consumers by reversing Trump Administration decisions that allowed on-demand pay providers to impose unfettered fees.

"Viewing earned wage advances, especially fee-based ones, as something other than credit will lead to evasion of consumer protection and fair lending laws," the group wrote in its Oct. 12 letter to the CFPB. It will also "lead to the same cycle of repeat reborrowing as other balloon-payment loans, and may lead to difficulties meeting future expenses or large bills such as rent or other monthly expenses."

In response, a CFPB said by email: "We have received the letter, and we appreciate this coalition's input."

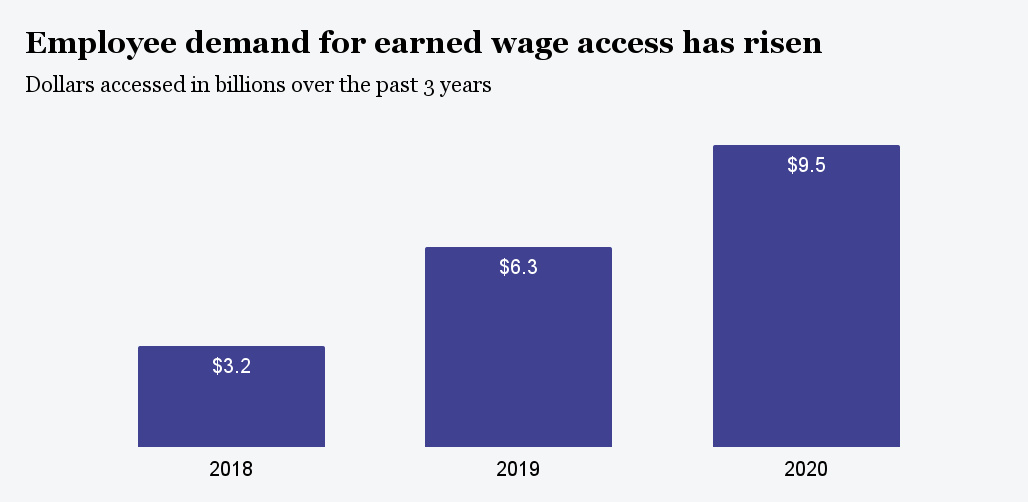

The issue has taken on more importance as workers increasingly use earned wage access (EWA) services. U.S. households tapped such services nearly 56 million times last year for about $9.5 billion in pay under such employer-based programs, according to estimates from research firm Aite-Novarica. In addition, millions more have downloaded apps that provide cash advances on their pay without employer participation, the firm said in a February report on the trend.

The services "are just a kinder version of payday loans," National Consumer Law Center Associate Director Lauren Saunders said in an interview last week regarding the coalition's CFPB petition.

Meanwhile, industry infighting is creating a divide between companies that offer the services through employers and rivals that sell directly to employees without the benefit of employer data or oversight. There's much at stake for companies that don't want to be tarnished by the practices of competitors and that may or may not benefit from more regulation in an increasingly competitive marketplace.

The debate over the issue turns on whether the early distribution of wages is a loan.

Under the Trump Administration, the CFPB last November issued an advisory opinion determining that EWA services offered by employers at no cost to them aren't an extension of credit and therefore aren't covered by the Truth in Lending Act. The following month, the CFPB also exempted Payactiv, one of the pioneers in the EWA business, from lending laws.

The advocates' coalition disagreed with those decisions and urged the CFPB to reassess the policies in its letter. "When we saw those actions, we were very concerned because we thought they were wrong," Saunders said. "We thought the legal reasoning was very sloppy."

By contrast, Payactiv CEO and co-founder Safwan Shah lauded the December decision as a "watershed moment" for the company, according to a report from industry trade publication Pymnts.com.

"It's very expensive to be poor," Shah said in a June interview with Payments Dive as he lambasted predatory payday loans and $35 bank overdraft fees. "Somebody had to get up and do something."

San Jose-based Payactiv, a pioneer of the industry founded in 2012, sells its services through some of the biggest U.S. payroll service providers, including Automatic Data Processing (ADP) and Paychex.

On-demand pay providers contend they're democratizing access to earnings for cash-strapped Americans faced with emergency expenses and saving them from predatory lenders' exorbitant fees and interest rates. Their business models differ, with some charging employers and others charging employees, and still others earning money from merchant interchange fees incurred when employees use debit cards issued under the programs.

For their part, employers increasingly see the programs as a tool to recruit and retain workers, especially in the current tight labor market. It may be an even more compelling benefit in light of the deadly COVID-19 pandemic increasing some workers' financial needs.

Under its approach, Payactiv floats money to an employee early and is repaid by the employer later, on the scheduled payday. The employer and the employee get the service for free if the employee moves the money to a debit card that lets Payactiv earn interchange fees. If the employee moves the wages to a different card or account, Payactiv charges $1 to $1.99 per distribution. Payactiv also lets employees apply wages directly to certain services, like rides from taxi-alternative Uber.

Shah, an engineer-turned-entrepreneur, says 80-plus million people in America living paycheck-to-paycheck need such services to avoid paying $300 in monthly late fees and bank overdraft charges. "If you are paid less, you must be paid more frequently," Shah argues.

Dozens of companies have entered the industry, many with backing from venture capitalists eager to profit from the growing trend. Branch, Gusto, FlexWage, Instant Financial, and Clair are among them.

Instant Financial Chief Operating Officer Steve Barha estimates there are at least 35 vendors in North America offering some form of EWA service. His Atlanta-based company, founded in 2015, counts 350 companies as clients, including Carnival Corp. and Outback Steakhouse parent Bloomin' Brands.

Instant Financial provides employees who opt into its employer-sponsored program a Visa debit card with real-time access to their earned wages. Instant Financial receives a portion of the merchant interchange fees on the spending when they use the card. Under Instant Financial's model, neither the employees nor the employer pay for the service. Barha argues that's the "right" approach for the industry.

"Now that there's so many using services like Instant, it's become kind of front-and-center for the regulators," Barha said in a September interview, noting he's spent hours talking to state and federal regulators.

"We feel that we have nothing here to hide," he said. Some programs are more "nefarious," and there should be regulations requiring clear disclosure of program fees and interest rates. "As long as we're protecting employees in their most financially vulnerable moment, I think we're just fine," Barha said.

At Even, Executive Chairman Jon Schlossberg, who co-founded the Oakland, California-based company in 2014, said problems emerged as new players arrived.

"They profit from desperation," he said in an August interview, without identifying any of them. "Financial services, and payments especially, are full of great businesses that like to pretend they're helping people."

Retailer Walmart, digital payments company PayPal, health insurer Humana and restaurant chain Noodles & Co., are among Even's customers. About half of Even's employer-clients absorb the total cost of EWA services provided to employees, but the other half of its clients charge employees based on their usage. Even's services are designed for hourly workers who can use its digital tools to manage their cash flow, Schlossberg said.

Nonetheless, consumer activists argue that EWA services can saddle employees with mounting fees as they access pay early and trap them in a cycle of rising indebtedness as they spend their money faster.

"Lobbyists for the earned wage access industry are using the Bureau's actions to promote exemptions from state usury and lending laws on the grounds that broad categories of products, regardless of price, are not credit," the coalition's letter said. "PayActiv is also using the CFPB order against competitors, claiming, misleadingly, that the CFPB has 'approved PayActiv's program' and that Payactiv's program 'is the only way to remain in compliance with the CFPB.'"

In response, Payactiv offered this statement from Payactiv General Counsel Aaron Marienthal by email: "The letter’s notion that consumers cannot be trusted to receive their own earned wages more than once or twice a month is at cross purposes with protecting and enabling the American worker.”

He also said the letter's characterization of EWA services misses the mark. Earned wage access products "allow employees to access wages they have already earned, and with Payactiv they can do so without paying any fee whatsoever. There is no debt."

Lawmakers in California, Utah, New Jersey, New York, Georgia, Nevada, North Carolina, and South Carolina debated EWA legislation with only California passing a law that impacted the industry.

In Utah, Republican Rep. James Dunnigan sponsored a law that he said would provide guidelines promoting the industry though there were "certain EWA companies that didn't want it to pass because they thought their way of doing it was the only true way."

Detractors said Dunnigan's proposal would squelch the popular new service, he explained. "It got caught up in a lot of misinformation," Dunnigan said. He asked companies why they opposed the bill, and they told him state regulations might spur federal action, he said.

Dunnigan identified New York-based DailyPay as the opposition's ringleader. He believed he had enough votes to pass it in the House Business and Labor Committee but backed off what had become a bigger battle than he expected, he said. Dunnigan isn't planning to back an alternative EWA version pending in the Utah State Senate, he said.

"DailyPay consistently supports all efforts by elected officials, including those in Utah, to protect consumers from harmful and predatory fintech practices," Matthew Kopko, DailyPay's vice president of public policy, said in an emailed statement, declining to comment further about the Utah situation.

In a post at the legal site J.D. Supra in May, Kopko, laid out a preference generally for less prescriptive EWA legislation. California's new law passed last year created a Department of Financial Protection and Innovation to oversee the industry and required EWA providers to file a memorandum of understanding with the state.

"California's DFPI showed great leadership with a flexible MOU process, which DailyPay joined, to help the State get a better handle on this emerging and fast-changing industry," Kopko said in the emailed statement, again declining to comment more broadly.

In his post, Kopko endorsed CFPB's advisory opinion. "It laid out a framework much more compatible with employer-based EWA programs, similar to those offered by leading EWA providers," Kopko wrote in the post. He labeled as "true" EWA programs those that "integrate with employers and offer the service as an employee benefit."

Kopko seemed to acknowledge increased regulation as inevitable. "With more and more of the Fortune 500 offering these programs, employer-based EWA is increasingly viewed as a mainstay of 21st-century payroll, and regulation will continue to catch up to where technology is heading," he wrote.

One key facet regulators are studying is whether employees use EWA programs in addition to predatory payday loans, or instead of them, said Leslie Parrish, a strategic advisor Aite-Novarica who authored the February report. In a survey of about 1,100 people using DailyPay, which commissioned the poll, Parrish determined that employees were mainly substituting EWA programs for predatory legacy options.

Parrish, who formerly worked for the CFPB and the Center for Responsible Lending, said the central question regulators are grappling with is whether EWA is a service or an extension of credit. The answer will determine whether federal and state regulators promote or curb the industry.

"Across the industry, there are a lot of different business models and they all have their pros and cons," Parrish said.

Consumer advocates concede that some EWA programs may be beneficial.

"Treating earned wage access products as credit does not mean that they should not exist," the coalition letter said. "Free or very low-cost programs that are repaid entirely through payroll deduction or otherwise without debiting bank accounts or delaying receipt of wages may be a better alternative to high-cost payday loans."

A regulatory shake-out may provide more clarity on best practices for all involved.

Correction: A quote from the consumer advocate coalition regarding Payactiv was corrected. The chart was corrected to show billions of dollars.